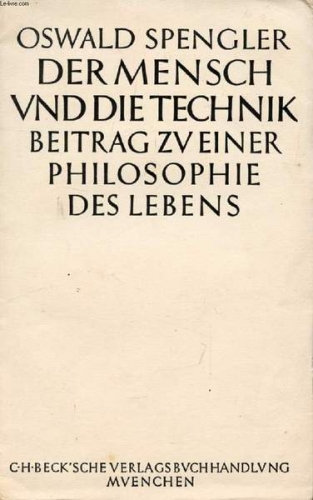

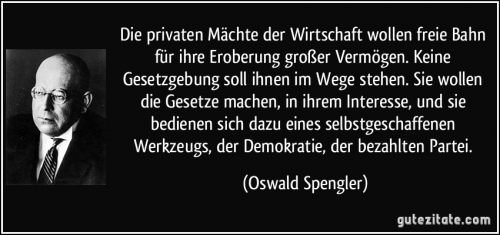

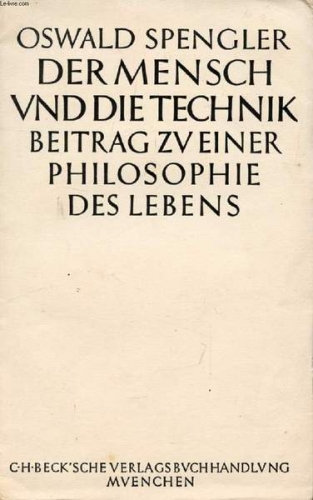

Oswald Spengler’s writings on the subject of the philosophy of science are very controversial, not only among his detractors but even for his admirers. What is little understood is that his views on these matters did not exist in a vacuum. Rather, Spengler’s arguments on the sciences articulate a long German tradition of rejecting English science, a tradition that originated in the eighteenth century.

Luke Hodgkin notes:

It is today regarded as a matter of historical fact that Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz both independently conceived and developed the system of mathematical algorithms known collectively by the name of calculus. But this has not always been the prevalent point of view. During the eighteenth century, and much of the nineteenth, Leibniz was viewed by British mathematicians as a devious plagiarist who had not just stolen crucial ideas from Newton, but had also tried to claim the credit for the invention of the subject itself.[1] [2]

This wrongheaded view stems from Newton’s own catty libel of Leibniz on these matters. During this time, the beginning of the eighteenth century, Leibniz’s native Prussia had not yet become a serious power through the wars of Frederick the Great. Leibniz, together with Frederick the Great’s grandfather, founded the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences. Newton’s slanderous account of Leibniz’s achievements would never be forgiven by the Germans, to whom Newton remained a bête noire as long as Germany remained a proud nation.

In the context of inquiring into the matter of how such a pessimist as Spengler could admire so notorious an optimist as Leibniz, two foreign members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences merit attention. The thought of French scientist and philosopher Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, an exponent and defender of Leibnizian ideas, was in many ways a precursor to modern biology. Maupertuis wrote under the patronage of Frederick the Great, about a generation after Leibniz. Compared to other eighteenth-century philosophies, Maupertuis’ worldview, like modern biology and unlike most Enlightenment thought, presents nature as rather “red in tooth and claw.”

An earlier foreign member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, a contemporary and correspondent of Leibniz, Moldavian Prince (and eccentric pretender to descent from Tamerlane) Dimitrie Cantemir, left two cultural legacies to Western history. Initially an Ottoman vassal, he gave traditional Turkish music its first system of notation, ushering in the classical era of Turkish music that would later influence Mozart. Later – after he had turned against the Ottoman Porte in an alliance with Petrine Russia, but was driven out of power and into exile due to his abysmal battlefield leadership – he wrote much about history. Most impactful in the West was a two-volume book that would be translated into English in 1734 as The History of the Growth and Decay of the Othman Empire. Voltaire and Gibbon later read Cantemir’s work, as did Victor Hugo.[2] [3]

Notes one biographer, “Cantemir’s philosophy of history is empiric and mechanistic. The destiny in history of empires is viewed . . . through cycles similar to the natural stages of birth, growth, decline, and death.”[3] [4] Long before Nietzsche popularized the argument, Cantemir proposed that high cultures are initially founded by barbarians, and also that a civilization’s level of high culture has nothing to do with its political success.[4] [5] Thus was the Leibnizian intellectual legacy mixed with pessimism even in Leibniz’s own lifetime.

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

By the early modern age of European history, when Goethe’s Faust takes place, cabalistic doctrines, notes Carl Schmitt, “became known outside Jewry, as can be gathered from Luther’s Table Talks, Bodin’s Demonomanie, Reland’s Analects, and Eisenmenger’s Entdecktes Judenthum.”[5] [6] This phenomenon can be traced to the indispensable influence of the very inventors of cabalism, collectively speaking, on the West’s transition from feudalism to modern capitalism since the Age of Discovery, and in some cases even earlier. In 1911’s The Jews and Modern Capitalism, Werner Sombart points out that “Venice was a city of Jews” as early as 1152.

Cabalism deeply permeates the worldviews of many influential secret societies of Western history since medieval times, and certainly continuing with the official establishment of Freemasonry in 1717. Although the details will never be entirely clear, it is known that Goethe was involved with the Bavarian Illuminati in his youth. He seems to have experienced conservative disillusionment with it later in life. It is possible that the posthumous publication of Faust: The Second Part of the Tragedy was due at least in part to the book’s ambivalently revealing too much about the esoterica of Goethe’s former occult activities.

What is clear is that he was directly interested in cabalistic concepts. Karin Schutjer persuasively argues that “Goethe had ample opportunity to learn about Jewish Kabbalah – particularly that of the sixteenth-century rabbi Isaac Luria – and good reason to take it seriously . . . Goethe’s interest in Kabbalah might have been further sparked by a prominent argument concerning its philosophical reception: the claim that Kabbalistic ideas underlie Spinoza’s philosophy.”[6] [7]

At one point in the second part of Faust, Goethe shows an interest in monetary issues related to usury or empty currency, as Schopenhauer after him would.[7] [8] This is fitting for a story that takes place in early modern Europe and concerns an alchemist. Some early modern alchemists were known as counterfeiters and would have most likely had contact with Jewish moneylenders. Insofar as his scientific philosophy had a social, and not just an intellectual, significance, this desire on Goethe’s part for economic concreteness was perhaps what led him to reject and combat one key cabalistic doctrine: numerology.

Numerology is the belief that numbers are divine and have prophetic power over the physical world. Goethe held the virtually opposite view of numbers and mathematical systems, proposing that “strict separation must be maintained between the physical sciences and mathematics.” According to Goethe, it is an “important task” to “banish mathematical-philosophical theories from those areas of physical science where they impede rather than advance knowledge,” and to discard the “false notion that a phrase of a mathematical formula can ever take the place of, or set aside, a phenomenon.” To Goethe, mathematics “runs into constant danger when it gets into the terrain of sense-experience.”[8] [9]

In his well-researched 1927 book on Freemasonry, General Erich Ludendorff remarks, “One must study the cabala in order to understand and evaluate the superstitious Jew correctly. He then is no longer a threatening opponent.”[9] [10] In his proceeding discussion of the subject, Ludendorff focuses exclusively on the numerological superstitions in cabalism. Such beliefs are affirmed by a Jewish cabalistic source, which informs us that “Sefirot” is the Hebrew word for numbers, which represent “a Tree of Divine Lights.”[10] [11]

Everything about Goethe’s rejection of scientific materialism can be seen as a rebellion against numerology in the sciences – and certainly, the modern mathematical sciences stand on the shoulders of numerology, as modern chemistry does on alchemy. Schmitt once mentioned the “mysterious Rosicrucian sensibility of Descartes,” a reference to the mysterious cabalistic initiatory movement that dominated the scientific philosophies of the seventeenth century.[11] [12] In this Descartes was hardly alone; the entire epoch of mostly French and English mathematicians in the early modern centuries, which ushered in the modern infinitesimal mathematical systems, was infused with cabalism. Even if it were possible to ignore the growing Jewish intellectual and economic influence on that age, one would still be left with the metaphysical affinities between numerology and even the most scientifically accomplished worldview that takes literally the assumption that numbers are eternal principles.

According to early National Socialist economist Gottfried Feder, “When the Babylonians overcame the Assyrians, the Romans the Carthaginians, the Germans the Romans, there was no continuance of interest slavery; there were no international world powers . . . Only the modern age with its continuity of possession and its international law allowed loan capitals to rise immeasurably.”[12] [13] Writing in 1919, Feder argues with the help of a graph that that “loan-interest capital . . . rises far above human conception and strives for infinity . . . The curve of industrial capital on the other hand remains within the finite!”[13] [14] Goethe may have similarly drawn connections between the kind of economic parasitism satirized in the second part of Faust and what he, like Berkeley, saw as the superstitious modern art of measuring the immeasurable.

The fusion of science with numerology, it should be noted, is actually not of Hebrew or otherwise pre-Indo-European origin. It originates from pre-Socratic Greek philosophy’s debt, particularly that of the Pythagoreans, to the Indo-Iranian world, chiefly Thrace.[14] [15] (Possibly of note in this regard is that Schopenhauer admired the Thracians for their arch-pessimistic ethos, as though this mindset were the polar opposite of the world-affirming Jewish worldview he loathed.)[15] [16] In any case, Goethe recognized it as a powerful weapon. That he studied numerology has been established by scholars.[16] [17]

A generation before Goethe, Immanuel Kant had propounded the idea that the laws of polarity – the laws of attraction and repulsion – precede the Newtonian laws of matter and motion in every way. This argument would influence Goethe’s friend Friedrich Wilhelm von Schelling, another innovator in the life sciences as well as part of the literary and philosophical movement known as Romanticism. By the time Goethe propounded his anti-Newtonian theories and led a philosophical milieu, he had an entire German tradition of such theories to work from.

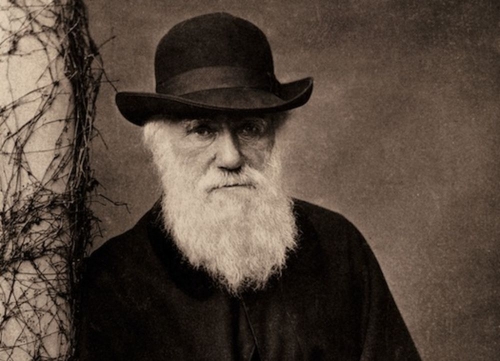

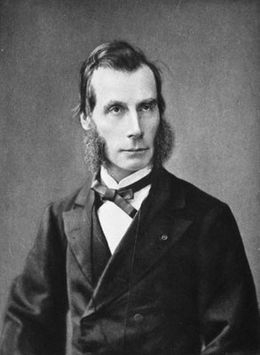

Goethe’s work was influential in Victorian Britain. Most notably, at least in terms of the scientific history of that era, Darwin would cite Goethe as a botanist in On the Origin of the Species. Darwin’s philosophy of science, to the extent that he had one, was largely built on that of Goethe and the age of what came to be known as Naturphilosophie. Historian of science Robert J. Richards has found that “Darwin was indebted to the Romantics in general and Goethe in particular.”[17] [18] Darwin had been introduced to the German accomplishments in biology, and the German ideas about philosophy of science, mainly through the work of Alexander von Humboldt.[18] [19]

Why has this influence been forgotten? “In the decade after 1918,” explains Nicholas Boyle, “when hundreds of British families of German origin were forcibly repatriated, and those who remained anglicized their names, British intellectual life was ethnically cleansed and the debt of Victorian culture to Germany was erased from memory, or ridiculed.”[19] [20] To some extent, this process had already started since the outbreak of the First World War.

This intellectual ethnic cleansing would not go unreciprocated. In 1915’s Händler und Helden (Merchants and Heroes), German economist and sociologist Werner Sombart attacked the “mercantile” English scientific tradition. Here, Sombart is particularly critical of what he calls the “department-store ethics” of Herbert Spencer, but in general Sombart calls for most English ideas – including English science – to be purged from German national life. In his writings on the philosophy of science, Spengler would answer this call.

Spengler heavily drew on the ideas of Goethe, and evidently also on the views of a pre-Darwinian French Lutheran paleontologist of German origin, Georges Cuvier. For instance, Spengler’s assault on universalism in the physical sciences mostly comes from Goethe, but his rationale for rejecting Darwinian evolution appears to come from Cuvier. The idea that life-forms are immutable, and simply die out, only to be superseded by unrelated new ones – a persistent theme in Spengler – comes more from Cuvier than Goethe.

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.[20] [21]

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.[20] [21]

Several asides about Cuvier are in order. First of all, this criminally underrated thinker is by no means outmoded, at least not in every way. Modern geology operates on a more-Cuvieran-than-Darwinian plane.[21] [22] Secondly, it is worth noting that Ernst Jünger once astutely observed that Cuvier is more useful to modern military science than Darwin.[22] [23] It may also be of interest that the Cuvieran system is even further removed from Lamarckism – and its view of heredity, as a consequence, more thoroughly racialist – than the Darwinian system.[23] [24]

Another scientist of German origin who may have influenced Spengler is the Catholic monk Gregor Mendel, the discoverer of what is now known as genetics. One biography notes:

Though Mendel agreed with Darwin in many respects, he disagreed about the underlying rationale of evolution. Darwin, like most of his contemporaries, saw evolution as a linear process, one that always led to some sort of better product. He did not define “better” in a religious way – to him, a more evolved animal was no closer to God than a less evolved one, an ape no morally better than a squirrel – but in an adaptive way. The ladder that evolving creatures climbed led to greater adaption to the changing world. If Mendel believed in evolution – and whether he did remains a matter of much debate – it was an evolution that occurred within a finite system. The very observation that a particular character trait could be expressed in two opposing ways – round pea versus angular, tall plant versus dwarf – implied limits. Darwin’s evolution was entirely open-ended; Mendel’s, as any good gardener of the time could see, was closed.[24] [25]

How very Goethean – and Spenglerian.

His continuation of the German mission against English science explains, even if it does not entirely excuse, Spengler’s citation of Franz Boas’ now-discredited experiments in craniology in the second volume of The Decline of the West. In his posthumously-published book on Indo-Europeanology, the unfinished but lucid Frühzeit der Weltgeschichte, Spengler cites the contemporary German Nordicist race theorist Hans F. K. Günther in writing that “urbanization is racial decay.”[25] [26] This would seem quite a leap, from citing Boas to citing Günther. However, in the opinion of one historian, Boas and Günther had more in common than they liked to think, because they were both heirs more of the German Idealist tradition in science than what the Anglo-Saxon tradition recognizes as the scientific method.[26] [27] Spengler must have keenly detected this commonality, for his views on racial matters were never synonymous with those of Boas, any more than they were identical to Günther’s.

He probably went too far in his crusade against the Anglo-Saxon scientific tradition, but as we have seen, Spengler was not without his reasons. He was neither the first nor the greatest German philosopher of science to present alternatives to the ruling English paradigms in the sciences, but was rather an heir to a grand tradition. Before dismissing this anti-materialistic tradition as worthless, as today’s historiographers of science still do, we should take into account what it produced.

Darwin’s philosophy of nature was predominantly German; only his Malthusianism, the least interesting aspect of Darwin’s work, was singularly British. As for Einstein, that proficient but unoriginal thinker was absolutely steeped in the German anti-Newtonian tradition, to which he merely put a mathematical formula. These are only the most celebrated examples of scientists influenced by the German tradition defended – maniacally, perhaps, but with noble intentions – in the works of Oswald Spengler.

Whether we consider Spengler’s ideas useful to science or utterly hateful to it, one question remains: Should the German tradition of philosophy of science he defended be taken seriously? Ever since the post-Second World War de-Germanization of Germany, euphemistically called “de-Nazification,” this tradition is now pretty much dead in its own fatherland. But does that make it entirely wrong?

Notes

[1] [28] Luke Hodgkin, A History of Mathematics: From Mesopotamia to Modernity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[2] [29] See the booklet of the CD Istanbul: Dimitrie Cantemir, 1630-1732, written by Stefan Lemny and translated by Jacqueline Minett.

[3] [30] Eugenia Popescu-Judetz, Prince Dimitrie Cantemir: Theorist and Composer of Turkish Music (Istanbul: Pan Yayıncılık, 1999), p. 34.

[4] [31] Dimitrie Cantemir, The History of the Growth and Decay of the Othman Empire, vol. I, tr. by Nicholas Tindal (London: Knapton, 1734), p. 151, note 14.

[5] [32] Carl Schmitt, The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes: Meaning and Failure of a Political Symbol, tr. by George Schwab and Erna Hilfstein (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), p. 8.

[6] [33] Karin Schutjer, “Goethe’s Kabbalistic Cosmology [34],” Colloquia Germanica, vol. 39, no. 1 (2006).

[7] [35] J. W. von Goethe, Faust, Part Two, Act I, “Imperial Palace” scene; Schopenhauer, The Wisdom of Life, Chapter III, “Property, or What a Man Has.”

[8] [36] Jeremy Naydler (ed.), Goethe on Science: An Anthology of Goethe’s Scientific Writings (Edinburgh: Floris Books, 1996), pp. 65-67.

[9] [37] Erich Ludendorff, The Destruction of Freemasonry Through Revelation of Their Secrets (Mountain City, Tn.: Sacred Truth Publishing), p. 53.

[10] [38] Warren Kenton, Kabbalah: The Divine Plan (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), p. 25.

[11] [39] Schmitt, Leviathan, p. 26.

[12] [40] Gottfried Feder, Manifesto for Breaking the Financial Slavery to Interest, tr. by Alexander Jacob (London: Black House Publishing, 2016), p. 38.

[13] [41] Ibid., pp. 17-18.

[14] [42] See, i.e., Walter Wili, “The Orphic Mysteries and the Greek Spirit,” collected in Joseph Campbell (ed.), The Mysteries: Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1955).

[15] [43] Arthur Schopenhauer, tr. by E. F. J. Payne, The World as Will and Representation, vol. II (Mineola, N.Y.: Dover, 2014), p. 585.

[16] [44] Ronald Douglas Gray, Goethe the Alchemist (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 6.

[17] [45] Robert J. Richards, The Romantic Conception of Life: Philosophy and Science in the Age of Goethe (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010), p. 435.

[18] [46] Ibid, pp. 518-526.

[19] [47] Nicholas Boyle, Goethe and the English-speaking World: Essays from the Cambridge Symposium for His 250th Anniversary (Rochester, N.Y.: Camden House, 2012), p. 12.

[20] [48] Oswald Spengler, tr. by Charles Francis Atkinson, The Decline of the West vol. II (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928), p. 31.

[21] [49] Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p. 94.

[22] [50] From Jünger’s Aladdin’s Problem: “It is astounding to see how inventiveness grows in nature when existence is at stake. This applies to both defense and pursuit. For every missile, an anti-missile is devised. At times, it all looks like sheer braggadocio. This could lead to a stalemate or else to the moment when the opponent says, ‘I give up’, if he does not knock over the chessboard and ruin the game. Darwin did not go that far; in this context, one is better off with Cuvier’s theory of catastrophes.”

[23] [51] See Georges Cuvier, Essay on the Theory of the Earth (London: Forgotten Books, 2012), pp. 125-128 & pp. 145-165.

[24] [52] Robin Marantz Henig, The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2017), p. 125.

[25] [53] Oswald Spengler, Frühzeit der Weltgeschichte (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1966), Fragment 101.

[26] [54] Amos Morris-Reich, “Race, Ideas, and Ideals: A Comparison of Franz Boas and Hans F. K. Günther [55],” History of European Ideas, vol. 32, no. 3 (2006).

De eersten die de omslag maken zijn de oude Grieken in de klassieke Oudheid. Griekenland bestaat uit vele stadstaten, maar de zeemacht Athene en de landmacht Sparta steken in deze Griekse wereld boven allen uit. Het denken van de Grieken veranderde van een volk dat zich enkel met landbouw bezighield naar een zeemacht, omdat het op een gegeven moment het gehele oostelijke deel van de Middellandse zee ging beheersen. De Grieken waren opgesloten in deze context en ze misten de mankracht om hieruit te breken.

De eersten die de omslag maken zijn de oude Grieken in de klassieke Oudheid. Griekenland bestaat uit vele stadstaten, maar de zeemacht Athene en de landmacht Sparta steken in deze Griekse wereld boven allen uit. Het denken van de Grieken veranderde van een volk dat zich enkel met landbouw bezighield naar een zeemacht, omdat het op een gegeven moment het gehele oostelijke deel van de Middellandse zee ging beheersen. De Grieken waren opgesloten in deze context en ze misten de mankracht om hieruit te breken.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.

Writing in 1963, Oliver avoids mention of Yockey’s “culture-distorter” or the Jewish Question (although he makes a nod to that Birchite proxy, the International Communist Conspiracy). Years later, with the “Birch Business” well behind him,

Writing in 1963, Oliver avoids mention of Yockey’s “culture-distorter” or the Jewish Question (although he makes a nod to that Birchite proxy, the International Communist Conspiracy). Years later, with the “Birch Business” well behind him,

Avec M. Macron, prête-nom ou fidéicommis d’une syndication de grands intérêts (ceux qui l’ont propulsé sans coup férir aux commandes du paquebot en perdition « France ») nous voyons clairement que l’homme a été évidemment parachuté à son poste… Qu’il ne s’est pas hissé à la force du poignet par le laborieux truchement des partis. Ces paniers de crabes écumant avec leurs tripatouillages, leurs magouilles, les copinages, les parrainages et les affiliations plus ou moins discrètes. Tout cela est révolu, vieux jeu, ringard. Aux orties les partis qui ne servent plus à rien, pas même à servir de caisse de résonance ou d’exutoire à la France populaire et moribonde, celle des usines délocalisées, des friches industrielles et des zones rurales livrées à l’agro-industrie mondialisée… Toutes choses et secteurs dont la nouvelle aristocratie cosmopolitiste n’a que faire et ne rêve que de placer en sédation profonde à coup d’allocs et de drogues dites douces en libre accès (du ballon rond à la marie-jeanne) !

Avec M. Macron, prête-nom ou fidéicommis d’une syndication de grands intérêts (ceux qui l’ont propulsé sans coup férir aux commandes du paquebot en perdition « France ») nous voyons clairement que l’homme a été évidemment parachuté à son poste… Qu’il ne s’est pas hissé à la force du poignet par le laborieux truchement des partis. Ces paniers de crabes écumant avec leurs tripatouillages, leurs magouilles, les copinages, les parrainages et les affiliations plus ou moins discrètes. Tout cela est révolu, vieux jeu, ringard. Aux orties les partis qui ne servent plus à rien, pas même à servir de caisse de résonance ou d’exutoire à la France populaire et moribonde, celle des usines délocalisées, des friches industrielles et des zones rurales livrées à l’agro-industrie mondialisée… Toutes choses et secteurs dont la nouvelle aristocratie cosmopolitiste n’a que faire et ne rêve que de placer en sédation profonde à coup d’allocs et de drogues dites douces en libre accès (du ballon rond à la marie-jeanne) !

Yo también lo creo, y en esto coincido con Fernández de la Mora. Nos hace falta una filosofía, y no una filosofía cualquiera. Nos hace falta una filosofía positiva. Entiéndaseme bien: positiva no significa positivista. De esta otra ya andamos sobrados. No faltan columnistas, periodistas, científicos sociales y naturales, expertos en "H" o en "B", que lanzan al aire y a las masas la carnaza positivista de que la "filosofía no sirve para nada" y venden la baratija de que, a lo sumo, un mero análisis lógico y lingüístico de los enunciados es cuanto queda por hacer al filósofo profesional. Eso, o la divulgación generalista, el trenzado ideológico-partidista o la labor anticuaria de rescatar y exponer "ideas del pasado". El neopositivismo anglosajón y colonizador fue parte del recado atlantista que nos llegó tras la "apertura" de nuestro país a la ayuda y a la influencia angloamericana en pleno franquismo, y se tradujo en la creación masiva de cátedras y plazas docentes de una filosofía –- la "analítica" –- que no era nuestra y que nada nos decía. Pudo ser una alternativa "modernizadora" ante el acartonamiento escolástico de la universidad franquista, es cierto, un acicate, siempre saludable, para estudiar lógica formal o interesarse por la epistemología de las ciencias "duras", pero poco más.

Yo también lo creo, y en esto coincido con Fernández de la Mora. Nos hace falta una filosofía, y no una filosofía cualquiera. Nos hace falta una filosofía positiva. Entiéndaseme bien: positiva no significa positivista. De esta otra ya andamos sobrados. No faltan columnistas, periodistas, científicos sociales y naturales, expertos en "H" o en "B", que lanzan al aire y a las masas la carnaza positivista de que la "filosofía no sirve para nada" y venden la baratija de que, a lo sumo, un mero análisis lógico y lingüístico de los enunciados es cuanto queda por hacer al filósofo profesional. Eso, o la divulgación generalista, el trenzado ideológico-partidista o la labor anticuaria de rescatar y exponer "ideas del pasado". El neopositivismo anglosajón y colonizador fue parte del recado atlantista que nos llegó tras la "apertura" de nuestro país a la ayuda y a la influencia angloamericana en pleno franquismo, y se tradujo en la creación masiva de cátedras y plazas docentes de una filosofía –- la "analítica" –- que no era nuestra y que nada nos decía. Pudo ser una alternativa "modernizadora" ante el acartonamiento escolástico de la universidad franquista, es cierto, un acicate, siempre saludable, para estudiar lógica formal o interesarse por la epistemología de las ciencias "duras", pero poco más. Las quejas de G. Fernández de la Mora, así como sus proyectos modernizadores, han quedado en el olvido. El cambio de Régimen, desde el franquismo (sistema en el cual éste pensador fue destacado miembro, e incluso ministro) hacia la Restauración borbónico-constitucional (R78) supuso el olvido e incluso la postergación de su obra. El filósofo conservador, pero en absoluto fascista, había concebido una España moderna en el plano científico y tecnológico, una España en la cual primaran el mérito, la capacidad, la preparación, y en donde se proscribiera para siempre la demagogia, el juego doctrinario, la retórica verbal y el patetismo. Es una voz la de Fernández de la Mora que no ha sido escuchada. Una España que la escuchara, será una nación radicalmente otra, renovada y sin prejuicios.

Las quejas de G. Fernández de la Mora, así como sus proyectos modernizadores, han quedado en el olvido. El cambio de Régimen, desde el franquismo (sistema en el cual éste pensador fue destacado miembro, e incluso ministro) hacia la Restauración borbónico-constitucional (R78) supuso el olvido e incluso la postergación de su obra. El filósofo conservador, pero en absoluto fascista, había concebido una España moderna en el plano científico y tecnológico, una España en la cual primaran el mérito, la capacidad, la preparación, y en donde se proscribiera para siempre la demagogia, el juego doctrinario, la retórica verbal y el patetismo. Es una voz la de Fernández de la Mora que no ha sido escuchada. Una España que la escuchara, será una nación radicalmente otra, renovada y sin prejuicios. Fernández de la Mora proclamaba sustituir las ideologías, ya moribundas, por ideas. Trocar a los demagogos y a los declamadores por expertos. En vez de entusiasmo, peligroso explosivo que siempre deviene en tiranía, consenso. El consenso tácito y la deliberación fría deben ocupar su puesto rector en lugar de la asamblea tumultuaria. El análisis sosegado de proyectos racionales en vez de agitación y propaganda. Qué duda cabe que la filosofía positiva no corrió la mejor de las fortunas una vez desembocada la partidocracia del R78. El régimen constitucional postfranquista ensalzó la retórica partidista y encumbró a un sinfín de ideólogos, retóricos vanos, arribistas, vividores "liberados" de los sindicatos y de los aparatos electoralistas. Los expertos, las personas formadas en las distintas ramas de la vida orgánica del Estado (administradores, expertos juristas, tecnólogos, economistas planificadores…) hubieron de ceder sus sillas o pasar a un discreto y segundo plano ante el soberano imperio de los grandilocuentes vendedores de humo. Incluso dentro de la democracia postfranquista se advierten claramente dos generaciones: una, primera, aún bien acreditada en cuanto a titulación académica y experiencia práctica en la empresa pública o en la privada, y otra, segunda, en la que ahora más y más nos hundimos, en la cual el lumpen de la sociedad, los sectores sociales más refractarios al esfuerzo intelectual, profesional y, en general, humano, se dedican, con el carnet en la boca, a ascender por los aparatos electoralistas para conseguir aplausos fáciles y cargos sine cura.

Fernández de la Mora proclamaba sustituir las ideologías, ya moribundas, por ideas. Trocar a los demagogos y a los declamadores por expertos. En vez de entusiasmo, peligroso explosivo que siempre deviene en tiranía, consenso. El consenso tácito y la deliberación fría deben ocupar su puesto rector en lugar de la asamblea tumultuaria. El análisis sosegado de proyectos racionales en vez de agitación y propaganda. Qué duda cabe que la filosofía positiva no corrió la mejor de las fortunas una vez desembocada la partidocracia del R78. El régimen constitucional postfranquista ensalzó la retórica partidista y encumbró a un sinfín de ideólogos, retóricos vanos, arribistas, vividores "liberados" de los sindicatos y de los aparatos electoralistas. Los expertos, las personas formadas en las distintas ramas de la vida orgánica del Estado (administradores, expertos juristas, tecnólogos, economistas planificadores…) hubieron de ceder sus sillas o pasar a un discreto y segundo plano ante el soberano imperio de los grandilocuentes vendedores de humo. Incluso dentro de la democracia postfranquista se advierten claramente dos generaciones: una, primera, aún bien acreditada en cuanto a titulación académica y experiencia práctica en la empresa pública o en la privada, y otra, segunda, en la que ahora más y más nos hundimos, en la cual el lumpen de la sociedad, los sectores sociales más refractarios al esfuerzo intelectual, profesional y, en general, humano, se dedican, con el carnet en la boca, a ascender por los aparatos electoralistas para conseguir aplausos fáciles y cargos sine cura. Don Gonzalo despedía con alegría al tipo de político retórico y declamador, pero experto en nada, que había dominado la escena pública europea durante todo el siglo XIX y que aún prolongaba su inútil existencia en el XX. A la par, el filósofo bendecía en "El Crepúsculo de las Ideologías" al tecnócrata, al experto, al "conocedor" que no busca encandilar a las masas, manipularlas y tocar las fibras de su entusiasmo, sino ser eficaz servidor público que plantea objetivos realistas en orden a una mejora del bienestar general, haciendo del Estado una maquinaria ágil, inteligente, bien engrasada. Una maquinaria que ha de renunciar, bajo riesgo de recaer en el ideologismo y en el utopismo más peligrosos, a reformar al hombre.

Don Gonzalo despedía con alegría al tipo de político retórico y declamador, pero experto en nada, que había dominado la escena pública europea durante todo el siglo XIX y que aún prolongaba su inútil existencia en el XX. A la par, el filósofo bendecía en "El Crepúsculo de las Ideologías" al tecnócrata, al experto, al "conocedor" que no busca encandilar a las masas, manipularlas y tocar las fibras de su entusiasmo, sino ser eficaz servidor público que plantea objetivos realistas en orden a una mejora del bienestar general, haciendo del Estado una maquinaria ágil, inteligente, bien engrasada. Una maquinaria que ha de renunciar, bajo riesgo de recaer en el ideologismo y en el utopismo más peligrosos, a reformar al hombre. Un ejemplo de cómo esta filosofía de ideas y no de utopías ideológicas perdió la batalla, y el vicio del ideologismo alcanzó el triunfo, fue el rosario de las reformas educativas de la democracia. Cada nueva ley de educación, comenzando con la barbarie de la LOGSE, hasta llegar a la actual LOMCE, demostró ser la consagración del ideologismo. En lugar de dotar al Estado de ideas, ideas tonificantes, hemos tenido ideología y más ideología. España necesitaba ideas en el sentido filosófico, esto es, conceptos generales (trans-categoriales) que hundieran sus raíces en los más variados conceptos y categorías científicas y técnicas, ideas que, debidamente entretejidas, formaran un proyecto comunitario para "poner a punto" nuestra sociedad y vuelvan a "ajustar" debidamente a España en el orden internacional, colocándola en el puesto que le compete y que se merece ateniéndose a su Historia y a su Presente. Pues bien, en lugar de eso, hemos sido víctimas de los pedagogos, esto es, de los ideólogos, que de manera harto interesada nos equipararon a todos por lo bajo, sustituyendo el imperativo del esfuerzo por la "integración" y halagando al vago y al parásito, con la esperanza de que sean muchedumbre los que sigan depositando en los mismos ataúdes ideológicos el voto mayoritario de los borregos.

Un ejemplo de cómo esta filosofía de ideas y no de utopías ideológicas perdió la batalla, y el vicio del ideologismo alcanzó el triunfo, fue el rosario de las reformas educativas de la democracia. Cada nueva ley de educación, comenzando con la barbarie de la LOGSE, hasta llegar a la actual LOMCE, demostró ser la consagración del ideologismo. En lugar de dotar al Estado de ideas, ideas tonificantes, hemos tenido ideología y más ideología. España necesitaba ideas en el sentido filosófico, esto es, conceptos generales (trans-categoriales) que hundieran sus raíces en los más variados conceptos y categorías científicas y técnicas, ideas que, debidamente entretejidas, formaran un proyecto comunitario para "poner a punto" nuestra sociedad y vuelvan a "ajustar" debidamente a España en el orden internacional, colocándola en el puesto que le compete y que se merece ateniéndose a su Historia y a su Presente. Pues bien, en lugar de eso, hemos sido víctimas de los pedagogos, esto es, de los ideólogos, que de manera harto interesada nos equipararon a todos por lo bajo, sustituyendo el imperativo del esfuerzo por la "integración" y halagando al vago y al parásito, con la esperanza de que sean muchedumbre los que sigan depositando en los mismos ataúdes ideológicos el voto mayoritario de los borregos.

Mais Fustel décrit la corvée démocratique au jour le jour (pp.451-452) :

Mais Fustel décrit la corvée démocratique au jour le jour (pp.451-452) :

It is at this point that we can both thank Jouvenel for the model he provides and also reject his attempts to adapt this system of insights to a defense of mixed governance in book VI.

It is at this point that we can both thank Jouvenel for the model he provides and also reject his attempts to adapt this system of insights to a defense of mixed governance in book VI. Jouvenel further elaborates on this with the following: “the monarchy, through its lawyers, comes between the barons and their subjects; the purpose is to compel the former to limit themselves to the dues which are customary and to abstain from arbitrary taxation.”

Jouvenel further elaborates on this with the following: “the monarchy, through its lawyers, comes between the barons and their subjects; the purpose is to compel the former to limit themselves to the dues which are customary and to abstain from arbitrary taxation.” In asking such a question, the focus of our attention must therefore shift from popular considerations of liberalism as a rational discourse conducted over many centuries to which the assent of reasonable and rational agents was won, to instead a consideration of it as being the result of institutional actions. In effect, we go from the Whig theory of history, Progress etc. to one which identifies modernity as the cultural result of institutional conflict.

In asking such a question, the focus of our attention must therefore shift from popular considerations of liberalism as a rational discourse conducted over many centuries to which the assent of reasonable and rational agents was won, to instead a consideration of it as being the result of institutional actions. In effect, we go from the Whig theory of history, Progress etc. to one which identifies modernity as the cultural result of institutional conflict. As for Larry Siedentop, his work on the history of the individual constantly gropes at outlining the mechanism Jouvenel provides, which is arguably the cause of the invention of the individual that he traces. There is no reason to assume that the mechanism of using the rhetoric of individualism and equality as a means to undermine competing power centers began with the Reformation, and Siedentop confirms it did not. It appears to be a constant of human political structure. Siedentop provides a point by point history of the process of the development of the concept of the individual as being a moral development driven by Church authorities and then by secular authorities (at which point we have liberalism). Siedentop does this by continually employing an understanding of early Christian European society as being essentially corporatist, with the Church engaging in a process of breaking down this feudal structure using fundamentally anarchist conceptions of society based on the invention of the individual. Siedentop’s account is essentially Jouvenelian without realizing it. We can even catch him making the Jouvenelian observation on ancient developments leading up to the invention of the individual:

As for Larry Siedentop, his work on the history of the individual constantly gropes at outlining the mechanism Jouvenel provides, which is arguably the cause of the invention of the individual that he traces. There is no reason to assume that the mechanism of using the rhetoric of individualism and equality as a means to undermine competing power centers began with the Reformation, and Siedentop confirms it did not. It appears to be a constant of human political structure. Siedentop provides a point by point history of the process of the development of the concept of the individual as being a moral development driven by Church authorities and then by secular authorities (at which point we have liberalism). Siedentop does this by continually employing an understanding of early Christian European society as being essentially corporatist, with the Church engaging in a process of breaking down this feudal structure using fundamentally anarchist conceptions of society based on the invention of the individual. Siedentop’s account is essentially Jouvenelian without realizing it. We can even catch him making the Jouvenelian observation on ancient developments leading up to the invention of the individual: It clearly wasn’t mere chance that this popular agitation occurred; it was clearly encouraged and allowed space by the secular rulers. It was the result of competing power centers wresting control from one another. The tool of individualizing was taken from the Church’s hands and used against it. Jouvenel implies that these preachers would have had institutional support. And in the case of John Wycliffe, he had the powerful sponsorship of John of Gaunt, the de facto king of England. This has puzzled historians greatly, but it does not puzzle us. As for Jan Hus, we have the Archbishop of Prague Zbyněk Zajíc and then King Wenceslaus IV. It seems to be a general law that all of these anti-clerical reformists were also pro-secular government and under the protection of patrons in the process of centralizing power and in chronic conflict with ecclesiastical authorities. They all ended in confiscation of Church property. Both Martin Luther and William of Ockham provide excellent additional examples.

It clearly wasn’t mere chance that this popular agitation occurred; it was clearly encouraged and allowed space by the secular rulers. It was the result of competing power centers wresting control from one another. The tool of individualizing was taken from the Church’s hands and used against it. Jouvenel implies that these preachers would have had institutional support. And in the case of John Wycliffe, he had the powerful sponsorship of John of Gaunt, the de facto king of England. This has puzzled historians greatly, but it does not puzzle us. As for Jan Hus, we have the Archbishop of Prague Zbyněk Zajíc and then King Wenceslaus IV. It seems to be a general law that all of these anti-clerical reformists were also pro-secular government and under the protection of patrons in the process of centralizing power and in chronic conflict with ecclesiastical authorities. They all ended in confiscation of Church property. Both Martin Luther and William of Ockham provide excellent additional examples.

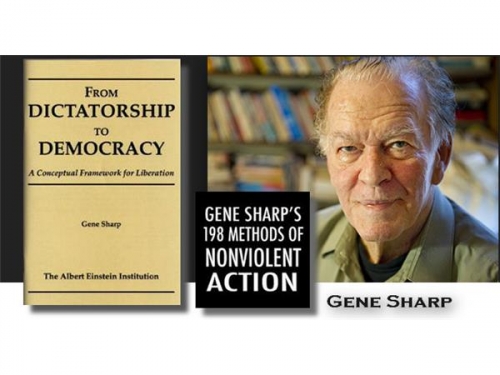

Dans cette optique, la résistance autochtone peut mener une multitude d’actions non-violentes : blocages momentanés de certains nœuds routiers, autoroutiers ou ferroviaires ; résistance fiscale ; boycott des élections ; lobbying ; constitution de ZAD identitaires ; interpellation d’élus républicains ; sit-in ; occupation d’écoles ; manifestations ; harcèlement ; etc. Il n’y a de limites que notre imagination… et l’étendue du Grand Rassemblement, c’est-à-dire des forces disponibles.

Dans cette optique, la résistance autochtone peut mener une multitude d’actions non-violentes : blocages momentanés de certains nœuds routiers, autoroutiers ou ferroviaires ; résistance fiscale ; boycott des élections ; lobbying ; constitution de ZAD identitaires ; interpellation d’élus républicains ; sit-in ; occupation d’écoles ; manifestations ; harcèlement ; etc. Il n’y a de limites que notre imagination… et l’étendue du Grand Rassemblement, c’est-à-dire des forces disponibles.

Chez ces deux auteurs, politique et religion sont mises ensemble, dans un même camp, dans une lutte opposant le bien au mal, même si ce qui représente le bien chez l’un représente le mal chez l’autre. Pour Schmitt, dans ce combat, le bourgeois est celui qui ne pense qu’à sa sécurité et qui veut retarder le plus possible son engagement dans ce combat entre bien et mal. Ce que le bourgeois considère comme le plus important, c’est sa sécurité, sécurité physique, sécurité de ses biens, comme de ses actions, «protection contre toute ce qui pourrait perturber l’accumulation et la jouissance de ses possessions» (p22). Il relègue ainsi dans la sphère privée la religion, et se centre ainsi sur lui-même. Or contre cette illusoire sécurité, Schmitt, et c’est là une thèse importante défendue par l’auteur, met au centre de l’existence la certitude de la foi («Seule une certitude qui réduit à néant toutes les sécurités humaines peut satisfaire le besoin de sécurité de Schmitt; seule la certitude d’un pouvoir qui surpasse radicalement tous les pouvoirs dont dispose l’homme peut garantir le centre de gravité morale sans lequel on ne peut mettre un terme à l’arbitraire: la certitude du Dieu qui exige l’obéissance, qui gouverne sans restriction et qui juge en accord avec son propre droit. (…) La source unique à laquelle s’alimentent l’indignation et la polémique de Schmitt est sa résolution à défendre le sérieux de la décision morale. Pour Schmitt, cette résolution est la conséquence et l’expression de sa théologie politique» (p24).). Et c’est dans cette foi que s’origine l’exigence d’obéissance et de décision morale. Schmitt croit aussi, comme il l’affirme dans sa Théologie politique, que «la négation du péché originel détruit tout ordre social».

Chez ces deux auteurs, politique et religion sont mises ensemble, dans un même camp, dans une lutte opposant le bien au mal, même si ce qui représente le bien chez l’un représente le mal chez l’autre. Pour Schmitt, dans ce combat, le bourgeois est celui qui ne pense qu’à sa sécurité et qui veut retarder le plus possible son engagement dans ce combat entre bien et mal. Ce que le bourgeois considère comme le plus important, c’est sa sécurité, sécurité physique, sécurité de ses biens, comme de ses actions, «protection contre toute ce qui pourrait perturber l’accumulation et la jouissance de ses possessions» (p22). Il relègue ainsi dans la sphère privée la religion, et se centre ainsi sur lui-même. Or contre cette illusoire sécurité, Schmitt, et c’est là une thèse importante défendue par l’auteur, met au centre de l’existence la certitude de la foi («Seule une certitude qui réduit à néant toutes les sécurités humaines peut satisfaire le besoin de sécurité de Schmitt; seule la certitude d’un pouvoir qui surpasse radicalement tous les pouvoirs dont dispose l’homme peut garantir le centre de gravité morale sans lequel on ne peut mettre un terme à l’arbitraire: la certitude du Dieu qui exige l’obéissance, qui gouverne sans restriction et qui juge en accord avec son propre droit. (…) La source unique à laquelle s’alimentent l’indignation et la polémique de Schmitt est sa résolution à défendre le sérieux de la décision morale. Pour Schmitt, cette résolution est la conséquence et l’expression de sa théologie politique» (p24).). Et c’est dans cette foi que s’origine l’exigence d’obéissance et de décision morale. Schmitt croit aussi, comme il l’affirme dans sa Théologie politique, que «la négation du péché originel détruit tout ordre social». La confrontation politique apparaît comme constitutive de notre identité. A ce titre, elle ne peut pas être seulement spirituelle ou symbolique. Cette confrontation politique trouve son origine dans la foi, qui nous appelle à la décision («La foi selon laquelle le maître de l’histoire nous a assigné notre place historique et notre tâche historique, et selon laquelle nous participons à une histoire providentielle que nos seules forces humaines ne peuvent pas sonder, une telle foi confère à chacun en particulier un poids qui ne lui est accordé dans aucun autre système: l’affirmation ou la réalisation du «propre» est en elle-même élevée au rang d’une mission métaphysique. Etant donné que le plus important est «toujours déjà accompli» et ancré dans le «propre», nous nous insérons dans la totalité compréhensive qui transcende le Je précisément dans la mesure où nous retournons au «propre» et y persévérons. Nous nous souvenons de l’appel qui nous est lancé lorsque nous nous souvenons de «notre propre question»; nous nous montrons prêts à faire notre part lorsque nous engageons ma confrontation avec «l’autre, l’étranger» sur «le même plan que nous» et ce «pour conquérir notre propre mesure, notre propre limite, notre propre forme.»« (p77-78).).

La confrontation politique apparaît comme constitutive de notre identité. A ce titre, elle ne peut pas être seulement spirituelle ou symbolique. Cette confrontation politique trouve son origine dans la foi, qui nous appelle à la décision («La foi selon laquelle le maître de l’histoire nous a assigné notre place historique et notre tâche historique, et selon laquelle nous participons à une histoire providentielle que nos seules forces humaines ne peuvent pas sonder, une telle foi confère à chacun en particulier un poids qui ne lui est accordé dans aucun autre système: l’affirmation ou la réalisation du «propre» est en elle-même élevée au rang d’une mission métaphysique. Etant donné que le plus important est «toujours déjà accompli» et ancré dans le «propre», nous nous insérons dans la totalité compréhensive qui transcende le Je précisément dans la mesure où nous retournons au «propre» et y persévérons. Nous nous souvenons de l’appel qui nous est lancé lorsque nous nous souvenons de «notre propre question»; nous nous montrons prêts à faire notre part lorsque nous engageons ma confrontation avec «l’autre, l’étranger» sur «le même plan que nous» et ce «pour conquérir notre propre mesure, notre propre limite, notre propre forme.»« (p77-78).). D’une part, Schmitt reproche à Hobbes d’artificialiser l’Etat, d’en faire un Léviathan, un dieu mortel à partir de postulats individualistes. En effet, ce qui donne la force au Léviathan de Hobbes, c’est une somme d’individualités, ce n’est pas quelque chose de transcendant, ou plus précisément, transcendant d’un point de vue juridique, mais pas métaphysique. A cette critique, il faut ajouter que, créé par l’homme, l’Etat n’a aucune caution divine: créateur et créature sont de même nature, ce sont des hommes. Or ces hommes, véritables individus prométhéens, font croire à l’illusion d’un nouveau dieu, né des hommes, et mortels, dont l’engendrement provient du contrat social. Et cette création à partir d’individus et non d’une communauté au sein d’un ordre voulu par Dieu, comme c’était, selon Hobbes, le cas au moyen-âge, perd par là-même sa légitimité aux yeux d’une théologie politique ( C. Schmitt écrit ainsi que: «ce contrat ne s’applique pas à une communauté déjà existante, créée par Dieu, à un ordre préexistant et naturel, comme le veut la conception médiévale, mais que l’Etat, comme ordre et communauté, est le résultat de l’intelligence humaine et de son pouvoir créateur, et qu’il ne peut naître que par le contrat en général.»).

D’une part, Schmitt reproche à Hobbes d’artificialiser l’Etat, d’en faire un Léviathan, un dieu mortel à partir de postulats individualistes. En effet, ce qui donne la force au Léviathan de Hobbes, c’est une somme d’individualités, ce n’est pas quelque chose de transcendant, ou plus précisément, transcendant d’un point de vue juridique, mais pas métaphysique. A cette critique, il faut ajouter que, créé par l’homme, l’Etat n’a aucune caution divine: créateur et créature sont de même nature, ce sont des hommes. Or ces hommes, véritables individus prométhéens, font croire à l’illusion d’un nouveau dieu, né des hommes, et mortels, dont l’engendrement provient du contrat social. Et cette création à partir d’individus et non d’une communauté au sein d’un ordre voulu par Dieu, comme c’était, selon Hobbes, le cas au moyen-âge, perd par là-même sa légitimité aux yeux d’une théologie politique ( C. Schmitt écrit ainsi que: «ce contrat ne s’applique pas à une communauté déjà existante, créée par Dieu, à un ordre préexistant et naturel, comme le veut la conception médiévale, mais que l’Etat, comme ordre et communauté, est le résultat de l’intelligence humaine et de son pouvoir créateur, et qu’il ne peut naître que par le contrat en général.»).

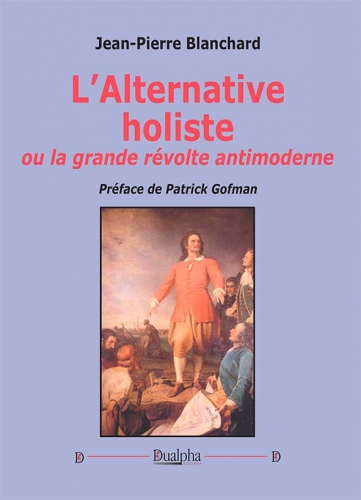

En 2014, dans le sillage de la « Manif pour Tous », Gaultier Bès se faisait connaître par Nos limites. Pour une écologie radicale, un essai co-écrit avec Marianne Durano et Axel Nørgaard Rokvam. Le succès de cet ouvrage lui permit de lancer en compagnie de la journaliste du groupe Le Figaro, Eugénie Bastié, et de Paul Piccarreta, la revue trimestrielle d’écologie intégrale d’expression chrétienne Limite.

En 2014, dans le sillage de la « Manif pour Tous », Gaultier Bès se faisait connaître par Nos limites. Pour une écologie radicale, un essai co-écrit avec Marianne Durano et Axel Nørgaard Rokvam. Le succès de cet ouvrage lui permit de lancer en compagnie de la journaliste du groupe Le Figaro, Eugénie Bastié, et de Paul Piccarreta, la revue trimestrielle d’écologie intégrale d’expression chrétienne Limite. Dans sa préface, Jean-Pierre Raffin estime quant à lui que la radicalité « est une notion noble qui fait appel aux fondements, aux racines de notre être, de notre vie en société puisque l’être humain est un être social qui, dépourvu de liens, disparaît ou sombre dans la démence (p. 7) ». Gaultier Bès prévient aussi que « sans la profondeur de l’enracinement, la radicalité se condamne à n’agir qu’en surface et se dégrade en extrémisme. Sans la vigueur de la radicalité, l’enracinement n’est qu’un racornissement, qui, faute de lumière, conduit à l’atrophie (p. 16) ». Il se réfère beaucoup à la philosophe Simone Weil malgré une erreur sur l’année de son décès, 1943 et non 1944, en particulier à son célèbre essai sur l’Enracinement.

Dans sa préface, Jean-Pierre Raffin estime quant à lui que la radicalité « est une notion noble qui fait appel aux fondements, aux racines de notre être, de notre vie en société puisque l’être humain est un être social qui, dépourvu de liens, disparaît ou sombre dans la démence (p. 7) ». Gaultier Bès prévient aussi que « sans la profondeur de l’enracinement, la radicalité se condamne à n’agir qu’en surface et se dégrade en extrémisme. Sans la vigueur de la radicalité, l’enracinement n’est qu’un racornissement, qui, faute de lumière, conduit à l’atrophie (p. 16) ». Il se réfère beaucoup à la philosophe Simone Weil malgré une erreur sur l’année de son décès, 1943 et non 1944, en particulier à son célèbre essai sur l’Enracinement.

Gaultier Bès fait finalement trop confiance aux racines. Il a beau distinguer « l’image végétale des “ racines [à] celle, toute minérale, des “ sources ” (p. 25) », il se méprend puisque l’essence bioculturelle de l’homme procède à la fois aux racines, aux sources et aux origines. Ces dernières sont les grandes oubliées de son propos. Ce n’est toutefois qu’en prenant acte de cette tridimensionnalité que l’enracinement sera complet. Pourtant, il prend soin de préciser que « le global n’est pas l’universel, c’est l’extension d’un local hégémonique (p. 76) ». L’avertissement fait penser à l’opuscule du Comité invisible, À nos amis. Le local « est une contraction du global (4) ». « Il y a tout à perdre à revendiquer le local contre le global, estime le Comité invisible. Le local n’est pas la rassurante alternative à la globalisation, mais son produit universel : avant que le ne soit globalisé, le lieu où j’habite était seulement mon territoire familier, je ne le connaissais pas comme “ local ”. Le local n’est que l’envers du global, son résidu, sa sécrétion, et non ce qui peut le faire éclater (5). » Outre le collectif d’ultra-gauche, Guillaume Faye s’interrogeait sur l’ambivalence du concept. « L’enracinement doit […] se vivre comme point de départ, la patrie comme base pour l’action extérieure et non comme “ logés ” à aménager. Il faut se garder de vivre l’enracinement sous sa forme “ domestique ”, qui tend aujourd’hui à prévaloir : chaque peuple “ chez soi ” pacifiquement enfermé dans ses frontières; tous folkloriquement “ enracinés ” selon une ordonnance universelle. Ce type d’enracinement convient parfaitement aux idéologues mondialistes. Il autorise la construction d’une superstructure planétaire où s’intégreraient, privés de leur sens, normés selon le même modèle, les nouveaux “ enracinés ” (6). »

Gaultier Bès fait finalement trop confiance aux racines. Il a beau distinguer « l’image végétale des “ racines [à] celle, toute minérale, des “ sources ” (p. 25) », il se méprend puisque l’essence bioculturelle de l’homme procède à la fois aux racines, aux sources et aux origines. Ces dernières sont les grandes oubliées de son propos. Ce n’est toutefois qu’en prenant acte de cette tridimensionnalité que l’enracinement sera complet. Pourtant, il prend soin de préciser que « le global n’est pas l’universel, c’est l’extension d’un local hégémonique (p. 76) ». L’avertissement fait penser à l’opuscule du Comité invisible, À nos amis. Le local « est une contraction du global (4) ». « Il y a tout à perdre à revendiquer le local contre le global, estime le Comité invisible. Le local n’est pas la rassurante alternative à la globalisation, mais son produit universel : avant que le ne soit globalisé, le lieu où j’habite était seulement mon territoire familier, je ne le connaissais pas comme “ local ”. Le local n’est que l’envers du global, son résidu, sa sécrétion, et non ce qui peut le faire éclater (5). » Outre le collectif d’ultra-gauche, Guillaume Faye s’interrogeait sur l’ambivalence du concept. « L’enracinement doit […] se vivre comme point de départ, la patrie comme base pour l’action extérieure et non comme “ logés ” à aménager. Il faut se garder de vivre l’enracinement sous sa forme “ domestique ”, qui tend aujourd’hui à prévaloir : chaque peuple “ chez soi ” pacifiquement enfermé dans ses frontières; tous folkloriquement “ enracinés ” selon une ordonnance universelle. Ce type d’enracinement convient parfaitement aux idéologues mondialistes. Il autorise la construction d’une superstructure planétaire où s’intégreraient, privés de leur sens, normés selon le même modèle, les nouveaux “ enracinés ” (6). »

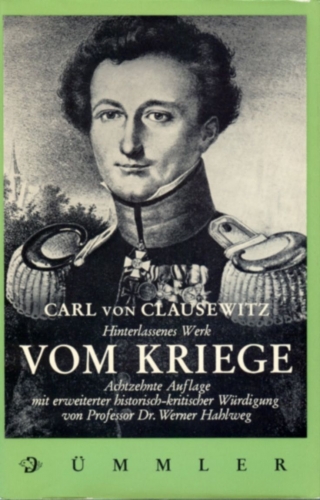

Oltre a questa differenza di fatto esistente nelle guerre, va stabilito in modo esplicito e preciso anche il punto di vista – pure praticamente necessario – secondo cui la guerra non è niente altro che la politica dello Stato proseguita con altri mezzi. Questo punto di vista, tenuto ben fermo dappertutto, darà unità a questa trattazione saggistica. E tutto sarà quindi più facile da districare.

Oltre a questa differenza di fatto esistente nelle guerre, va stabilito in modo esplicito e preciso anche il punto di vista – pure praticamente necessario – secondo cui la guerra non è niente altro che la politica dello Stato proseguita con altri mezzi. Questo punto di vista, tenuto ben fermo dappertutto, darà unità a questa trattazione saggistica. E tutto sarà quindi più facile da districare. Centrando il nostro pensiero sulla politica, per poi passare alla guerra, è necessario soffermarsi su questo punto. La politica è un conflitto di interessi, si fonda su di essi e si basa su rapporti di forza, vale a dire su rapporti tra individui che pensano e agiscono in modo da raggiungere i loro scopi. Sicché si può divergere per almeno due ragioni: si diverge sul fine o si diverge sul mezzo, o su entrambi. La politica ammette diversificazione di partiti non solo in virtù dello scopo finale, cioè un peculiare ordinamento sociale o economico, ma pure sui mezzi attraverso cui raggiungere lo scopo. I comunisti e i socialisti non avevano grandi distinzioni in merito ai fini, ma grandi differenze sussistevano nella concezione dei mezzi attraverso cui raggiungere gli scopi.

Centrando il nostro pensiero sulla politica, per poi passare alla guerra, è necessario soffermarsi su questo punto. La politica è un conflitto di interessi, si fonda su di essi e si basa su rapporti di forza, vale a dire su rapporti tra individui che pensano e agiscono in modo da raggiungere i loro scopi. Sicché si può divergere per almeno due ragioni: si diverge sul fine o si diverge sul mezzo, o su entrambi. La politica ammette diversificazione di partiti non solo in virtù dello scopo finale, cioè un peculiare ordinamento sociale o economico, ma pure sui mezzi attraverso cui raggiungere lo scopo. I comunisti e i socialisti non avevano grandi distinzioni in merito ai fini, ma grandi differenze sussistevano nella concezione dei mezzi attraverso cui raggiungere gli scopi. Ogni attore politico ammette tre generi di relazioni con un altro attore politico: alleanza, indifferenza, ostilità. Nel caso in cui le due parti in contrapposizione non trovino alcun genere di accordo possibile né sui fini da raggiungere, né sui mezzi, e sono propensi a darsi battaglia per ottenere la vittoria sull’altro, si giunge al conflitto. Se il conflitto è di natura sociale, si parla di lotta politica; se il conflitto è di natura armata, si parla di guerra. Politica e guerra sono solo due casi particolari della logica del conflitto e la guerra è, a sua volta, una peculiare forma della politica. Perché è solo l’interesse politico a determinare la volontà di combattere per mezzo delle armi.

Ogni attore politico ammette tre generi di relazioni con un altro attore politico: alleanza, indifferenza, ostilità. Nel caso in cui le due parti in contrapposizione non trovino alcun genere di accordo possibile né sui fini da raggiungere, né sui mezzi, e sono propensi a darsi battaglia per ottenere la vittoria sull’altro, si giunge al conflitto. Se il conflitto è di natura sociale, si parla di lotta politica; se il conflitto è di natura armata, si parla di guerra. Politica e guerra sono solo due casi particolari della logica del conflitto e la guerra è, a sua volta, una peculiare forma della politica. Perché è solo l’interesse politico a determinare la volontà di combattere per mezzo delle armi. Allo stesso tempo, con l’avanzare della tecnica e delle conoscenze scientifiche, le guerre cambiano di strumenti ma non nella sostanza. La natura dei fini umani è sempre la stessa, non cambia in base alle epoche storiche: ciò che cambia è l’oggetto, non l’intenzione verso di esso. In questo senso, la guerra, non solo nel suo farsi ma anche nel suo concetto, è di natura permanentemente multiforme. Essa cambia nei mezzi e negli scopi, cioè muta totalmente di forma. È la forma della guerra, non le sue ragioni profonde, a costituire la ragione fondamentale della diversità dei conflitti armati della storia. Eppure, a partire dalla comprensione della guerra nel suo ruolo di strumento politico, si nota una lunga linea di continuità tra i vari fenomeni bellici.

Allo stesso tempo, con l’avanzare della tecnica e delle conoscenze scientifiche, le guerre cambiano di strumenti ma non nella sostanza. La natura dei fini umani è sempre la stessa, non cambia in base alle epoche storiche: ciò che cambia è l’oggetto, non l’intenzione verso di esso. In questo senso, la guerra, non solo nel suo farsi ma anche nel suo concetto, è di natura permanentemente multiforme. Essa cambia nei mezzi e negli scopi, cioè muta totalmente di forma. È la forma della guerra, non le sue ragioni profonde, a costituire la ragione fondamentale della diversità dei conflitti armati della storia. Eppure, a partire dalla comprensione della guerra nel suo ruolo di strumento politico, si nota una lunga linea di continuità tra i vari fenomeni bellici.

Tout le monde a oublié Henri Lefebvre et je pensais que finalement il vaut mieux être diabolisé, dans ce pays de Javert, de flics de la pensée, qu’oublié. Tous les bons penseurs, de gauche ou marxistes, sont oubliés quand les réactionnaires, fascistes, antisémites, nazis sont constamment rappelés à notre bonne vindicte. Se rappeler comment on parle de Céline, Barrès, Maurras ces jours-ci… même quand ils disent la même chose qu’Henri Lefebvre ou Karl Marx (oui je sais, cent millions de morts communistes, ce n’est pas comme le capitalisme, les démocraties ou les Américains qui n’ont jamais tué personne, Dresde et Hiroshima étant transmuées en couveuses par la doxa historique).

Tout le monde a oublié Henri Lefebvre et je pensais que finalement il vaut mieux être diabolisé, dans ce pays de Javert, de flics de la pensée, qu’oublié. Tous les bons penseurs, de gauche ou marxistes, sont oubliés quand les réactionnaires, fascistes, antisémites, nazis sont constamment rappelés à notre bonne vindicte. Se rappeler comment on parle de Céline, Barrès, Maurras ces jours-ci… même quand ils disent la même chose qu’Henri Lefebvre ou Karl Marx (oui je sais, cent millions de morts communistes, ce n’est pas comme le capitalisme, les démocraties ou les Américains qui n’ont jamais tué personne, Dresde et Hiroshima étant transmuées en couveuses par la doxa historique). C’est dans l’ère des masses. On peut rajouter ce peu affriolant passage :

C’est dans l’ère des masses. On peut rajouter ce peu affriolant passage : Les pays comme la Chine qui ont renoncé au marxisme orthodoxe aujourd’hui avec un milliard de masques sur la gueule, de l’eau polluée pour 200 millions de personnes et des tours à n’en plus finir à vingt mille du mètre. Cherchez alors le progrès depuis Marco Polo…

Les pays comme la Chine qui ont renoncé au marxisme orthodoxe aujourd’hui avec un milliard de masques sur la gueule, de l’eau polluée pour 200 millions de personnes et des tours à n’en plus finir à vingt mille du mètre. Cherchez alors le progrès depuis Marco Polo… « La révolution… crée le genre d’homme qui lui sont nécessaires, elle développe cette race nouvelle, la nourrit d'abord en secret dans son sein, puis la produit au grand jour à mesure qu'elle prend des forces, la pousse, la case, la protège, lui assure la victoire sur tous les autres types sociaux. L'homme impersonnel, l’homme en soi, dont rêvaient les idéologues de 1789, est venu au monde : il se multiplie sous nos yeux, il n'y en aura bientôt plus d’autre ; c'est le rond-de-cuir incolore, juste assez instruit pour être « philosophe », juste assez actif pour être intrigant, bon à tout, parce que partout on peut obéir à un mot d'ordre, toucher un traitement et ne rien faire – fonctionnaire du gouvernement officiel - ou mieux, esclave du gouvernement officieux, de cette immense administration secrète qui a peut-être plus d'agents et noircit plus de paperasses que l'autre. »

« La révolution… crée le genre d’homme qui lui sont nécessaires, elle développe cette race nouvelle, la nourrit d'abord en secret dans son sein, puis la produit au grand jour à mesure qu'elle prend des forces, la pousse, la case, la protège, lui assure la victoire sur tous les autres types sociaux. L'homme impersonnel, l’homme en soi, dont rêvaient les idéologues de 1789, est venu au monde : il se multiplie sous nos yeux, il n'y en aura bientôt plus d’autre ; c'est le rond-de-cuir incolore, juste assez instruit pour être « philosophe », juste assez actif pour être intrigant, bon à tout, parce que partout on peut obéir à un mot d'ordre, toucher un traitement et ne rien faire – fonctionnaire du gouvernement officiel - ou mieux, esclave du gouvernement officieux, de cette immense administration secrète qui a peut-être plus d'agents et noircit plus de paperasses que l'autre. »

In his Parmenides, Martin Heidegger contributed an interesting remark in regards to the Greek term “polis”, which once again confirms the importance and necessity of serious etymological analysis. By virtue of its profundity, we shall reproduce this quote in full:

In his Parmenides, Martin Heidegger contributed an interesting remark in regards to the Greek term “polis”, which once again confirms the importance and necessity of serious etymological analysis. By virtue of its profundity, we shall reproduce this quote in full:

Gustave Le Bon affirme que l’évolution des institutions politiques, des religions ou des idéologies n’est qu’un leurre. Malgré des changements superficiels, une même âme collective continuerait à s’exprimer sous des formes différentes. Farouche opposant du socialisme de son époque, Gustave Le Bon ne croit pas pour autant au rôle de l’individu dans l’histoire. Il conçoit les peuples comme des corps supérieurs et autonomes dont les cellules constituantes sont les individus. La courte existence de chacun s’inscrit par conséquent dans une vie collective beaucoup plus longue. L’âme d’un peuple est le résultat d’une longue sédimentation héréditaire et d’une accumulation d’habitudes ayant abouti à l’existence d’un « réseau de traditions, d’idées, de sentiments, de croyances, de modes de penser communs » en dépit d’une apparente diversité qui subsiste bien sûr entre les individus d’un même peuple. Ces éléments constituent la synthèse du passé d’un peuple et l’héritage de tous ses ancêtres : « infiniment plus nombreux que les vivants, les morts sont aussi infiniment plus puissants qu’eux » (lois psychologiques de l’évolution des peuples). L’individu est donc infiniment redevable de ses ancêtres et de ceux de son peuple.

Gustave Le Bon affirme que l’évolution des institutions politiques, des religions ou des idéologies n’est qu’un leurre. Malgré des changements superficiels, une même âme collective continuerait à s’exprimer sous des formes différentes. Farouche opposant du socialisme de son époque, Gustave Le Bon ne croit pas pour autant au rôle de l’individu dans l’histoire. Il conçoit les peuples comme des corps supérieurs et autonomes dont les cellules constituantes sont les individus. La courte existence de chacun s’inscrit par conséquent dans une vie collective beaucoup plus longue. L’âme d’un peuple est le résultat d’une longue sédimentation héréditaire et d’une accumulation d’habitudes ayant abouti à l’existence d’un « réseau de traditions, d’idées, de sentiments, de croyances, de modes de penser communs » en dépit d’une apparente diversité qui subsiste bien sûr entre les individus d’un même peuple. Ces éléments constituent la synthèse du passé d’un peuple et l’héritage de tous ses ancêtres : « infiniment plus nombreux que les vivants, les morts sont aussi infiniment plus puissants qu’eux » (lois psychologiques de l’évolution des peuples). L’individu est donc infiniment redevable de ses ancêtres et de ceux de son peuple. La dilution des religions dans l’âme des peuples

La dilution des religions dans l’âme des peuples Ainsi, l’art de l’Egypte ancienne a irrigué la création artistique d’autres peuples pendant des siècles. Mais cet art, essentiellement religieux et funéraire et dont l’aspect massif et imperturbable rappelait la fascination des égyptiens pour la mort et la quête de vie éternelle, reflétait trop l’âme égyptienne pour être repris sans altérations par d’autres. D’abord communiqué aux peuples du Proche-Orient, cet art égyptien a inspiré les cités grecques. Mais Gustave Le Bon estime que ces influences égyptiennes ont irrigué ces peuples à travers le prisme de leur propre esprit. Tant qu’il ne s’est pas détaché des modèles orientaux, l’art grec s’est maintenu pendant plusieurs siècles à un stade de pâle imitation. Ce n’est qu’en se métamorphosant soudainement et en rompant avec l’art oriental que l’art grec connut son apogée à travers un art authentiquement grec, celui du Parthénon. A partir, d’un matériau identique qu’est le modèle égyptien transmis par les Perses, la civilisation indienne a abouti à un résultat radicalement différent de l’art grec. Parvenu à un stade de raffinement élevé dès les siècles précédant notre ère mais n’ayant que très peu évolué ensuite, l’art indien témoigne de la stabilité organique du peuple indien : « jusqu’à l’époque où elle fut soumis à la loi de l’islam, l’Inde a toujours absorbé les différents conquérants qui l’avaient envahie sans se laisser influencer par eux ».

Ainsi, l’art de l’Egypte ancienne a irrigué la création artistique d’autres peuples pendant des siècles. Mais cet art, essentiellement religieux et funéraire et dont l’aspect massif et imperturbable rappelait la fascination des égyptiens pour la mort et la quête de vie éternelle, reflétait trop l’âme égyptienne pour être repris sans altérations par d’autres. D’abord communiqué aux peuples du Proche-Orient, cet art égyptien a inspiré les cités grecques. Mais Gustave Le Bon estime que ces influences égyptiennes ont irrigué ces peuples à travers le prisme de leur propre esprit. Tant qu’il ne s’est pas détaché des modèles orientaux, l’art grec s’est maintenu pendant plusieurs siècles à un stade de pâle imitation. Ce n’est qu’en se métamorphosant soudainement et en rompant avec l’art oriental que l’art grec connut son apogée à travers un art authentiquement grec, celui du Parthénon. A partir, d’un matériau identique qu’est le modèle égyptien transmis par les Perses, la civilisation indienne a abouti à un résultat radicalement différent de l’art grec. Parvenu à un stade de raffinement élevé dès les siècles précédant notre ère mais n’ayant que très peu évolué ensuite, l’art indien témoigne de la stabilité organique du peuple indien : « jusqu’à l’époque où elle fut soumis à la loi de l’islam, l’Inde a toujours absorbé les différents conquérants qui l’avaient envahie sans se laisser influencer par eux ». La genèse des peuples

La genèse des peuples

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.